In this post, we looked at how many (Covid-19) tests one (Jon) would have to take to obtain a certain accuracy; Jon would need to test 9 times to obtain (more than) 99 $\%$ accuracy with a Covid-19 test that is 85 $\%$ accurate using the LRT based decision rule. To answer this question we did a power analysis to obtain the minimum number of tests we would need for our likelihood ratio test to attain a certain power.

However, we have not proved that this is the optimal test strategy in terms of cost i.e. that the likelihood ratio test is in fact the most efficient test. Efficiency is defined by the sample size, denoted $m^\ast$, needed to obtain the required accuracy. So to fully answer original question and obtain the minimal cost for Jon we need the test with the highest efficiency.

It turns out that several different groups of researchers during World War 2, as part of the war effort, were thinking about statistical efficiency, e.g. when testing batches of say military equipment, to minimize the cost associated. In particular the Statistical Research Group (SRG) at Columbia University, was working on this problem and it was apparently the economist Milton Friedman and economist and statistician Wilson Allen Wallis who as part of the group, conjectured that a so-called sequential strategy, where the final number of tests depends on the test outcomes, should in principle be more efficient than deciding on the number of test in advance as with the LRT, while obtaining the same error rates $\alpha$ and $\beta$.

The idea, you could say is is to treat the testing problem as an optimal stopping problem; we want to stop testing as soon as we have sufficient evidence to make a decision with a certain confidence (accuracy).

Optimal stopping problems are well known in mathematical finance, where the early exercise feature of an American option leads to this type of problem. In analogy, as is well-know from option theory, while European options, because of their fixed exercise time, have an analytical expression for their price, an American option does not. Both mathematically and computationally pricing an American option is much more complicated due to the optimal stopping problem embedded, however it is immediately clear that the American option is more valuable, due to the extra optionality.

Now, In the same way as early exercise for an American options can lead to a higher payoff hence higher price, early stopping for our testing problem may also lead to a lower cost for Jon compared to what we found in Part I where we determined the number of tests in advance. For instance in Jons example with a $85\%$ accurate test if you start out with 5 ones you already know that the majority of the required 9 tests is ones hence you do not need to perform the last 4 tests. Stopping early in this case would would then save Jon $32$. This shows that, given an appropriate stopping rule, it should be possible to obtain the accuracy we want but at a lower cost than in Part I . However, like with the American option, exactly what constitutes an optimal stopping rule is not obvious.

Wald

It was Abraham Wald, who was also part of the SRG, that after hearing about Friedman’s and Wallis conjecture, was the first to propose a mathematical framework, sequential probability ratio testing (SPRT), in which a stopping rule is derived for this type of testing problem. Later together with Jacob Wolfowitz he showed that his proposed stopping rule is also optimal for the simple hypothesis setting; It is the most efficient test for a given accuracy, see (Wald and Wolfowitz, 1948).

Note! In the following any notation not explained is from Part I.

To introduce the SPRT procedure and the all important stopping rule we do as in (Wald, 1945) and define the following two quantities

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{1}\label{eq6} b_0=\frac{\beta}{1-\alpha},\quad b_1=\frac{1-\beta}{\alpha}, \end{alignat}\]where we note that with $\alpha,\beta<0.5$ we have $0<b_0<1<b_1 $. Next consider the random variable defined by

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{2}\label{eq7} Z_j=\log\Big (\frac{f_{1}(T_j)}{f_{0}(T_j)}\Big )=\delta(2T_j-1), \end{alignat}\]with $T_1,T_2,\ldots$ Bernoulli i.i.d.. Then clearly $Z_1,Z_2,\ldots$ are i.i.d. with $Z_j\in\{-\delta,\delta\}$ and it follows that we can write $S_m$ from (3) in post I as

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{3}\label{eq8} S_m =\sum_{j=1}^m Z_j. \end{alignat}\]Then we can formalize the sequential probability likelihood ratio procedure.

Given the single test accuracy $a$ and desired error rates $\alpha$ and $\beta $ the constants $b_0$ and $b_1$ define the stopping rule; for each iteration if $S_m\geq \log(b_1)$ we stop and accept $\mathcal H_1$, if $S_m\leq \log(b_0)$ we stop and accept $ \mathcal H_0$ and otherwise we test one more time.

In machine learning terminology we can view the SPRT as an online (sequential) learning procedure and correspondingly the classical Neyman-Pearson LRT procedure as batch learning. The SPRT algorithm is optimal in the sense that on average it will use the fewest tests to accept a hypothesis compared to any other test attaining the same power. In particular, it turns out that using this type of online learning is much more efficient, often cutting the number of trials we need to perform on average in half compared to the batch learning approach.

To formalize this optimality notion and compute the expected number of trials Jon would have to do using the SPRT procedure define the stopping time

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} \tau =\inf\{n\in \mathbb N : S_n\leq \log(b_0) \text{ or } S_n\geq \log(b_1)\}. \end{alignat*}\]$\tau\in \mathbb N$ is a random variable giving the number of iterations Algorithm 1 will do before it stops, that is the number of test Jon has to carry out to obtain a Covid-19 test result with the desired accuracy. As shown in (Wald and Wolfowitz, 1948) the SPRT is optimal in that it minimizes $E_i(\tau)$, the expected time to acceptance under each hypothesis, for any desired accuracy level.

In our specific setup as we will show next, we can explicitly compute the number of times we have to test on average. To do this let $Z$ be a random variable with distribution identical to that of the i.i.d. variables $Z_1,\ldots,Z_j$ in \eqref{eq7}. Then from \eqref{eq8} and using Walds identity it follows that

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{4}\label{eq9} E_i(\tau)=\frac{E_i(S_\tau)}{E_i(Z)} . \end{alignat}\]For the denominator clearly

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{5}\label{eq10} E_i(Z)= \delta(2E_i(T_j)-1) =\left\{ \begin{array}{ccc} \delta(1-2a),& i=0& \\ - \delta(1-2a),& i=1.& \end{array} \right. \end{alignat}\]To compute the numerator, first observe that using Tower property (Adam’s Law?), since either $D_\tau=0$ or $D_\tau=1$, we get

\[\begin{alignat}{4} E_i(S_\tau)&= E_i(S_\tau\mid D_\tau=1)P_i(D_\tau=1)+E_i(S_\tau\mid D_\tau=0)P_i(D_\tau=0)\nonumber\\ &= E_i(S_\tau\mid D_\tau=1)(1-P_i(D_\tau=0))+E_i(S_\tau\mid D_\tau=0)P_i(D_\tau=0).\tag{6}\label{eq11} \end{alignat}\]Next since $\alpha$ is the probability of accepting $\mathcal H_0$ when $\mathcal H_1$ is true (under $P_1$) and $\beta$ is the probability of accepting $\mathcal H_1$ when $\mathcal H_0$ is true (under $P_0$) we have

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{7}\label{eq12} P_i(D_\tau=0)=\left\{ \begin{array}{ccc} 1-\beta,& i=0 \\ \alpha,& i=1. \\ \end{array} \right. \end{alignat}\]Then note that $S_m$ takes values in the set

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} \{-\delta m,-\delta(m-1),\ldots,-\delta,0,\delta, \ldots,\delta(m-1),\delta m\}, \end{alignat*}\]and with $a,\alpha,\beta$ given it is straightforward to determine $n_0,n_1\in \mathbb N$ such that

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{8}\label{eq13} n_i =\min\{n\in \mathbb N: n\delta \geq \vert \log(b_i) \vert\}. \end{alignat}\]Then as $\vert S_m-S_{m-1}\vert=\delta$, by definition of $\tau$, with unit probability under both $P_0$ and $P_1$

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{9}\label{eq14} S_\tau =\left\{ \begin{array}{ccc} -\delta n_0 ,&\text{given}& D_\tau=0 \\ \delta n_1,& \text{given}& D_\tau=1. \end{array} \right. \end{alignat}\]Combining \eqref{eq11}, \eqref{eq12} and \eqref{eq14} we obtain

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} E_i(S_\tau)&= \left\{ \begin{array}{ccc} \delta n_1\beta-\delta n_0(1-\beta) ,& i=0 \\ \delta n_1(1-\alpha)-\delta n_0\alpha,& i=1, \end{array} \right. \end{alignat*}\]and finally using \eqref{eq10} we can write \eqref{eq9} as

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} E_i(\tau) =\left\{ \begin{array}{ccc} \frac{ n_1 \beta- n_0(1-\beta)}{1-2a},& i=0 \\ \frac{ n_0\alpha- n_1(1-\alpha) }{ 1-2a},& i=1. \end{array} \right. \end{alignat*}\]In the special case with $\alpha=\beta=1-a^\ast$, such that we have overall test accuracy $a^\ast$, by \eqref{eq6} $b_1=1/b_0$ hence $\vert \log(b_1)\vert=\vert \log(b_0)\vert$ and by \eqref{eq13} we must have $n_0=n_1$. Finally if $n^\ast(a):=n_0=n_1$ denotes this common integer viewed as a function of $a$ then

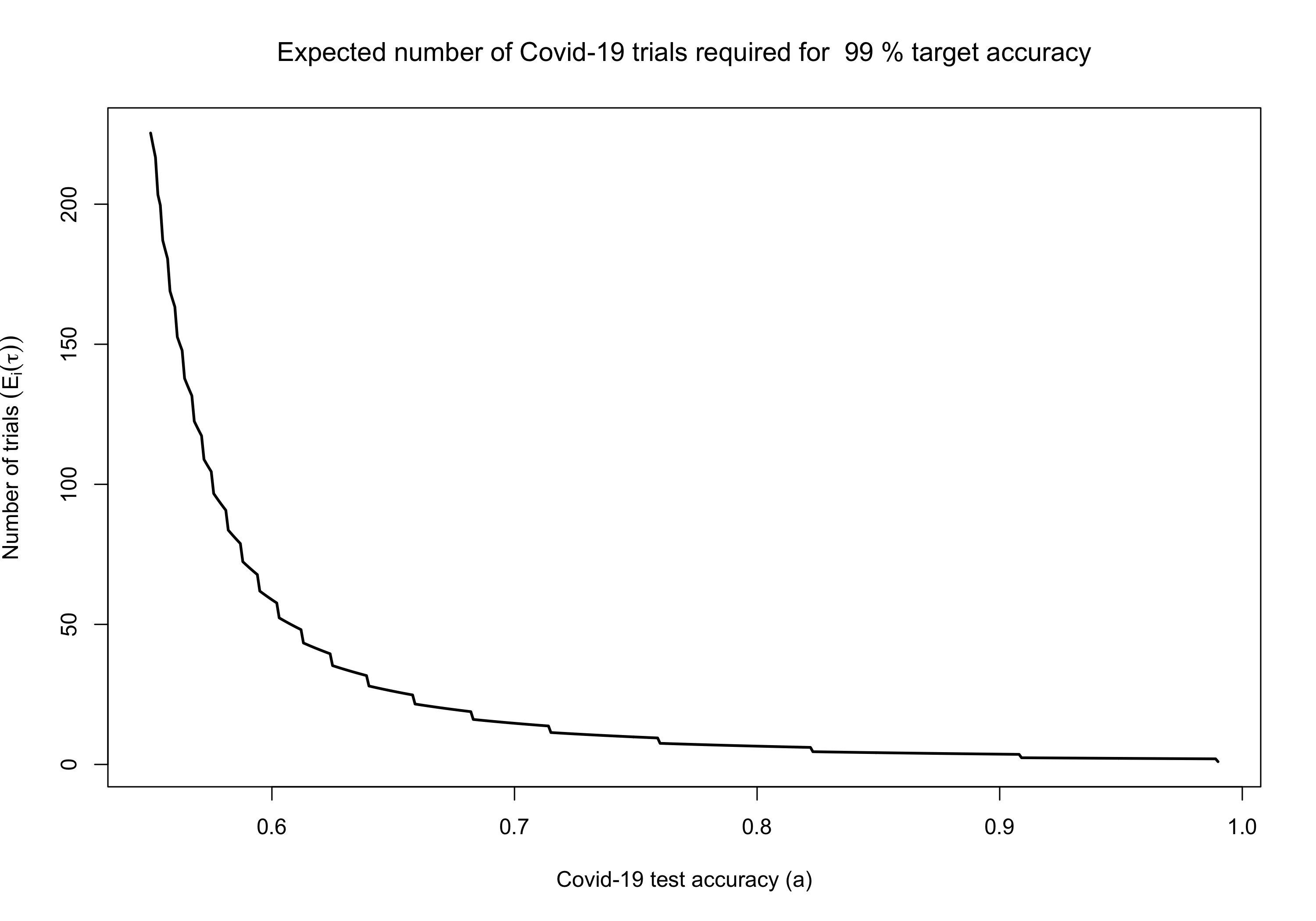

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{10}\label{eq15} E_0(\tau) = E_1(\tau) = \frac{ n^\ast(a)(1-a^\ast)-n^\ast(a)a^\ast }{ 1-2a} = n^\ast(a) \frac{ 1-2a^\ast }{ 1-2a}. \end{alignat}\]This expression gives us the number of tests we have to perform on average, as a function of the test accuracy $a$, to obtain target accuracy $a^\ast$. Furthermore this is the lowest number of tests on average for any test with error rates defined by $\alpha=\beta=1-a^\ast$, i.e. accuracy $a^\ast$.

Note that for $a=1/2$ \eqref{eq15} is infinite again reflecting that we do not learn anything by repeating a test that is correct half the time. Also for $a=a^\ast$ we get $\delta=\log(b_1)$ implying $n^\ast(a)=1$ by \eqref{eq13} and then $E_i(\tau)=1$ as expected. The following figure shows how the function in \eqref{eq15} looks for $a^\ast =0.99$.

In the table below we compare the values of $m^\ast$ for $a^\ast=0.99$, the trials needed when using the LRT, with the expected number of trials needed with the SPRT approach.

| $a$ | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $E(\tau)$ | 26.13 | 9.80 | 4.20 | 2.18 |

| $m^\ast$ | 57 | 19 | 9 | 3 |

We see that the SPRT easily cuts the number of tests required in half. In particular, Jon on average would have to test 4.2 times, costing him $33.6$, to get the desired $99\%$ accuracy using a $85\%$ accurate test.

References

Abraham Wald. Sequential tests of statistical hypotheses. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 16(2):117-186, 1945.

Abraham Wald and Jacob Wolfowitz. Optimum character of the sequential probability ratio test. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 19(3):326-339, 1948.