If Jon has 10000 covid-19 test kits with $85\%$ accuracy costing $£8$ a piece, assuming each test kit is drawn from an identical independent distribution (i.i.d.), how much does Jon need to spend to get $99\%$ accuracy?

A little while back a friend –a physicist of course– came up with this clever Covid-19 themed (job interview?) question for 2020. Now it sounds simple enough… or thinking about it a little at least intuitive; if Jon keeps testing he would gather evidence (learn), giving him more confidence in the overall test result. But how to formalize this very simple idea?

We start by noting two things. First of all accuracy in testing terminology is in fact composed of two different types of accuracies; true positive rate $a_1\in[0,1]$ (sensitivity) and the true negative rate $a_0\in[0,1]$ (specificity). To a doctor or a statistician these are the relevant quantities to have when describing the accuracy $a$ of a test which is then given by \begin{alignat}{4}\tag{1}\label{eq1} a = a_1\eta+a_0(1-\eta) \end{alignat} where $\eta\in[0,1]$ is the prevalence, i.e. the fraction of positive in the population.

In principle, an 85 $\%$ accuracy could come about by applying a covid19-test that always comes out negative if $\eta=0.15$ i.e 15 $\%$ of the population is positive. With such a test we cannot get a better accuracy (learn anything) by repeating it. We will assume that the i.i.d. test kits are correct a fraction (here $a$) of the time in the sense if any person (positive or negative) takes $m$ tests then on average $am$ will be correct and $(1-a)m$ incorrect. Based on this assumption, as we will see in this post, we can fairly easily come up with a solution to Jons problem relying on fundamental concepts from statistics, specifically the Neyman-Pearson Lemma.

There is a second issue however with the question; it is not completely clear if we are seeking the minimum amount Jon needs to pay or just some amount that would give him the required accuracy. It turns out that it is much more difficult to find the solution with the optimal (minimum) cost associated. This part of the problem concerns the statistical efficiency of the testing procedure and in a second post we show how to obtain the optimal solution to Jons testing problem using a procedure proposed by Abraham Wald.

Neyman and Pearson

Now, what we should do, is some how, given $m$ single trial covid-19 tests answers (data) $t_1,\ldots,t_m$ where $t_j\in\{0,1\}$ with $0$ meaning covid-19 negative, device an overall test $D_m\in\{0,1\}$, that with probability $a^\ast$, gives ud the correct diagnosis. But what does this test look like? How do we combine $m$ tests into one overall test $D_m$ in way that let us control the accuracy?

Thinking about it a little the problem does look a like a classical hypothesis testing situation. In particular we can let $\mathcal H_0$ (the null hypothesis) be the hypothesis that Jon is covid-19 negative and $\mathcal H_1$ (the alternative hypothesis) that Jon is covid-19 positive –that seems kind of obvious. Then what we are looking to do is, given $m$ observations $t_1,\ldots,t_m$, to figure out which hypothesis (model) is in concordance with these observations.

To introduce this concordance idea, let $P_i$ denote the probability distribution from which we draw the data $t_1,t_2,\ldots$ when $\mathcal H_i$ is the true hypothesis for $i\in \{0,1\}$. In other words $t_j$ is a realization of a random variable $T_j$ with distribution $P_i$ under $\mathcal H_i$. We then let $\alpha$ denote the probability of a false positive i.e. that our test determines Jon as positive when he is in fact negative (type I error) and $\beta$ the probability of making a false negative (type II error). Then for the overall test we have $a_1=P_1(D_m=1)=1-\beta$ and $a_0=P_0(D_m=0)=1-\alpha$.

We can already note two things. First we can assume that $\alpha,\beta\in(0,1/2)$ since otherwise we would be wrong more than half the time, when using $D_m$, implying we should reverse the test and consider $1-D_m$ instead. Secondly, by \eqref{eq1} if we want the overall accuracy when using the test $D_m$ to be $a^\ast$ for any prevalence $\eta \in [0,1]$ it follows we must have $\alpha=\beta$.

Now what is perhaps slightly confusing in our setup, compared to a usual simple hypothesis testing setup, is that apparently we do not seem to have a situation where we compare a hypothesis about a parameter in a distribution to a hypothesis about a different parameter in that same distribution. However, since by model assumption $T_j$ indicates the true diagnosis with probability $a$ it follows that given Jon is negative (i.e. under the null $\mathcal H_0$) we must have $P_0(T_j=0)=a$ hence $P_0(T_j=1)=1-a$. Similarly given Jon is positive (i.e. under the alternative) we must have $P_1(T_j=1)=a$. This means that with $t_j\in \{0,1\}$ the density (probability function for $T_j$) under $\mathcal H_0$ is $ f_{0}(t_j)=(1-a)^{t_j}a^{1-t_j}$ and under $\mathcal H_1$ it is $ f_{1}(t_j)=a^{t_j}(1-a)^{1-t_j}$ . Furthermore since the tests $T_1,T_2,\ldots$ are assumed i.i.d. it follows that their joint distribution is just the product of the marginals under each hypothesis. So under the null $\mathcal H_0$ we obtain the likelihood of the data is

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} f_0(t_1,\ldots,t_m) =\prod_{j=1}^mf_{0}(t_j) =(1-a)^{\sum_{i=1}^mt_i}a^{m-\sum_{i=1}^mt_i} \end{alignat*}\]and under the alternative $ \mathcal H_1$, the likelihood is

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} f_1(t_1,\ldots,t_m) =\prod_{j=1}^mf_{1}(t_j)= a^{\sum_{i=1}^mt_i}(1-a)^{m-\sum_{i=1}^mt_i}. \end{alignat*}\]So we see that we have a particularly simple version of a simple hypothesis setup for parameters $a$ and $1-a$.

Now classical statistic testing theory, that is the Neyman-Pearson Lemma, tells us that we should use the likelihood ratio test (LRT) quantity

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} L_m :=\frac{f_1(T_1,\ldots,T_m)}{f_0(T_1,\ldots,T_m)} =\frac{a^{\sum_{i=1}^mT_i}(1-a)^{m-\sum_{i=1}^mT_i}}{(1-a)^{\sum_{i=1}^mt_i}a^{m-\sum_{i=1}^mt_i}} =\Big(\frac{a}{1-a}\Big)^{2\sum_{i=1}^mT_i-m} \end{alignat*}\]when deciding which of the two hypothesis we should accept. The overall test or decision rule based on the $m$ observations is then

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{2}\label{eq2} D_m= \left\{ \begin{array}{cccc} 1& \text{if} & L_m> c \\ B&\text{if}& L_m= c \\ 0& \text{if} & L_m< c, \end{array} \right. \end{alignat}\]where $B\sim bern(q)$, $q\in [0,1]$. In particular $c$ and $q$ are determined such that the decision rule $D_m$ has statistical significance $\alpha$ (probability of false positive) i.e.

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} P_0(D_m=1)=P_0 ( L_m>c)+ q P_0( L_m=c)=\alpha. \end{alignat*}\]This decision rule is optimal in the following sense; it is the most powerful test (the lowest probability of making a type II error) at significance level $\alpha$, i.e the test that gives us the highest probability of rejecting a false null hypothesis.

Using \eqref{eq2} gives us a testing procedure but still leaves the question of how to obtain the desired accuracy. To answer that we need to know the distribution of our test quantity $L_m$ or, if thats not easy to figure out or a non-standard distribution, its asymptotical distribution. In our setup however, if we consider an equivalent decision rule based on the logarithm of the likelihood ratio $L_m$, we can obtain analytical expressions of the error probabilities.

So let us define the test quantity

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{3}\label{eq3new} S_m:=\log(L_m)= \delta\Big (2\sum_{j=1}^mT_j-m\Big) \end{alignat}\]where

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} \delta:= \log\Big (\frac{a}{1-a}\Big). \end{alignat*}\]Note that $\delta $ as a function of the accuracy $a$, quantifies the amount of information embedded in the test variable $T_j$, a little like the entropy if you will, and in turn indicates if we can learn anything from repeating the test (sampling $T_j$). As such we can think of $\delta$ as the learning rate of our overall test $D_m$. Maximal “entropy” is reached for $a=1/2$, the uniform binary distribution, yielding $\delta=0$ reflecting that repeating the test wont let us learn anything. On the other hand for $a=1$, (minimal entropy) $\delta=\infty$ reflecting that the learning procedure gives us the truth every time i.e. an oracle procedure. Note that $\vert \delta \vert$ is symmetric around $a=1/2$ reflecting that a binary test that is wrong more than half the time is just as good as a binary test that is right more than half the time.

Now if we compare $S_m$ to $\log(c)$ our decision variable becomes

\[\begin{alignat}{4}\tag{4}\label{eq3} D_m= \left\{ \begin{array}{cccc} 1& \text{if} & \sum_{i=1}^mT_i> \frac{m}{2}+\frac{\log(c)}{2\delta}\\ B&\text{if} & \sum_{i=1}^mT_i= \frac{m}{2}+\frac{\log(c)}{2\delta}\\ 0& \text{if} & \sum_{i=1}^mT_i< \frac{m}{2}+\frac{\log(c)}{2\delta}. \end{array} \right. \end{alignat}\]Clearly \eqref{eq3} is equivalent to \eqref{eq2} and makes intuitive sense. It shows directly that the threshold controlling the significance level (i.e. the accuracy of the test), for any fixed $c$, is in fact a function of the number of trials $m$. In particularly, it is convenient to choose $c=1$ to obtain the majority rule; after $m$ trials if the majority of answers are covid-19 positive we will reject the null and accept that Jon is postive, in case of a tie we will let chance decide and otherwise we will accept that he is negative.

Now what remains is to find $m^\ast$ such that the test procedure based on $\eqref{eq3}$ has accuracy $a^\ast$. This is easy since $\sum_{i=1}^mT_i$ is binomial distributed under each hypothesis. This means the probabilities of error, $\alpha =P_0(D_m=1)$ and $\beta=P_1(D_m=0)$, are easy to compute as a function of $m$ under each hypothesis.

In particular, the error probability $\alpha $ under $\mathcal H_0$ is

\[\begin{alignat}{4} P_0(& D_m=1)= P_0\Big(\sum_{i=1}^mT_i>\frac{m}{2}\Big)+q P_0\Big(\sum_{i=1}^mT_i=\frac{m}{2}\Big) \nonumber \\ &= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \sum_{i=m/2+1}^{m}\binom{m}{i}(1-a)^ia^{m-i}+q \binom{m}{m/2}(1-a)^{m/2}a^{m-m/2}&m \text{ is even}\\ \sum_{i=(m+1)/2}^{m}\binom{m}{i}(1-a)^ia^{m-i} &m \text{ is odd} \end{array} \right.\nonumber\\ &= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \sum_{j=0}^{m/2-1}\binom{m}{j}(1-a)^{m-j}a^{j}+q \binom{m}{m/2}((1-a)a)^{m/2}&m \text{ is even}\\ \sum_{j=0}^{(m-1)/2}\binom{m}{j}(1-a)^{m-j}a^{j} &m \text{ is odd}. \end{array} \right.\tag{5}\label{eq4} \end{alignat}\]The last expression is obtained by changing the index to $j:=m-i$ and using the fact that

\[\begin{alignat*}{4} \binom{m}{i}=\binom{m}{m-i},\quad i\in \{0,\ldots, m\}. \end{alignat*}\]Under $\mathcal H_1$ we get that the error probability $\beta$ is

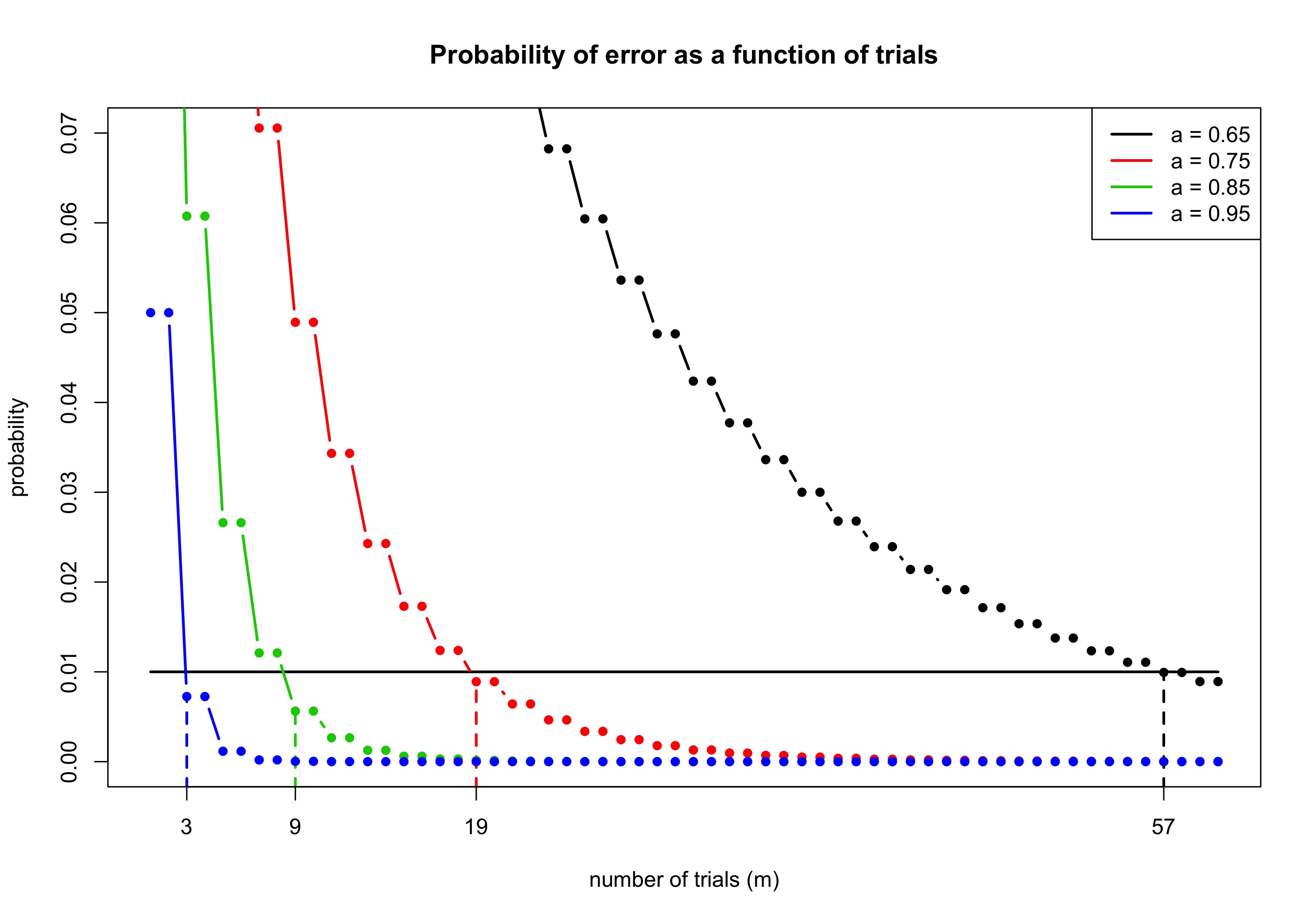

\[\begin{alignat}{4} P_1(& D_m=0)= P_1\Big(\sum_{i=1}^mT_i<\frac{m}{2}\Big)+(1-q) P_1\Big(\sum_{i=1}^mT_i=\frac{m}{2}\Big)\nonumber \\ &= \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \sum_{i=0}^{m/2-1}\binom{m}{j} a^{i}(1-a)^{m-i}+(1-q) \binom{m}{m/2} (a(1-a))^{m/2}&m \text{ is even}\\ \sum_{i=0}^{(m-1)/2}\binom{m}{j}a^i(1-a)^{m-i}&m \text{ is odd}. \end{array} \right.\tag{6}\label{eq5} \end{alignat}\]As noted initially to obtain overall accuracy $a^\ast$ for any prevalence level we must have $\alpha=\beta$ according to \eqref{eq1}. By \eqref{eq4} and \eqref{eq5} this happens if and only if $q=1-q$ implying we have to let $q=1/2$ in our test procedure. Now for fixed $q=1/2$ to finally determine $m^\ast $ we plot \eqref{eq5} as a function of $m$.

Note that the first time we obtain the desired accuracy is after an odd number of trials for each $a$, i.e. it is always suboptimal to test an even number of times. This is actually good information to have since some places indeed recommend that you test twice if you want higher confidence in the result. Using the decision rule \eqref{eq3}, this is not warranted.

Finally to help Jon, specifically for $a^\ast =0.99$ and $a=0.85$ he needs to test $m^\ast=9$ times for a total cost of $£72$. Doing that he actually gets around a $99.5 \%$ accuracy, however he can save $£16$ if he is willing to accept a slightly lower accuracy at around $98.8 \%$.

However we have not shown that this is the minimal cost given the desired target accuracy. Perhaps Jon can spend less, without compromising the overall test accuracy, if he used a different testing strategy?